Recent perspectives on American leadership: "stunningly strong position"; we "rue the rise of an 'America First' world"; hitting the "global snooze button"?; and a "new centrism" emerges in DC

Eric Peters, One River Asset Management: “US is in a stunningly strong position… this is America’s opportunity.”

Via CNBC’s Carl Quintanilla’s wonderful feed on Twitter/X over the weekend, I came across Eric Peters’ “wknd notes,” a unique newsletter that aggregates his thinking about the markets and politics. Eric Peters is the CEO and CIO of One River Asset Management, an alternatives investment firm with over $4B in AUM according to their latest SEC filing.

In his May 19th “wknd notes,” Peters analyzes the joint statement put out following Xi and Putin’s recent summit in Beijing. Quotes from the joint statement are in italics.

“The parties oppose the hegemonic attempts of the United States to change the balance of power in Northeast Asia by building up military power and creating military blocs and coalitions.”

The crack between East and West, the Global South and North, is rapidly widening. America’s competitors and adversaries appear to think that the window of opportunity is now open to divide the world before their collapsing demographics deny them any realistic chance of success. Given their trajectories, it is probably a risk worth taking for Putin and Xi.

“The China-Russia relationship today is hard-earned, and the two sides need to cherish and nurture it,” Xi told Putin during the press conference.

“China is willing to… jointly achieve the development and rejuvenation of our respective countries and work together to uphold fairness and justice in the world.”

And to win, the US must simply have faith that the weight of the world’s nations will follow our lead, if only we have the courage and determination to live up to our founding principles.

…

The Chinese/Russian joint statement reads like a playbook for how to create a fully independent political and economic zone.

For Taiwan - Russia reaffirms its commitment to the principle of ‘One China’, recognizes that Taiwan is an integral part of China, opposes the independence of Taiwan in any form, and firmly supports the actions of the Chinese side to protect its own sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as to unify the country.

For Ukraine - The Russian side positively assesses China's objective and unbiased position on the Ukrainian issue. China supports the efforts of the Russian side to ensure security and stability, national development and prosperity, sovereignty, and territorial integrity, and opposes outside interference in Russia's internal affairs.

…

The US is in a stunningly strong position in such a world, if only it can get out of its own way and be true to its founding principles. Liberty, equality, democracy, Republicanism, rule of law, separation of powers, checks and balances, individual rights, Federalism, natural rights, limited government, judicial review. The demographic implosion underway in both Russia and China will not be filled by ambitious immigrants, who uproot their families for a better life under those systems. They’ll come here. This is America’s opportunity.

Read the full ‘notes’ here.

Hal Brands, Foreign Affairs: “In time, the United States, too, would rue the rise of an ‘America first’ world — but only after so many other countries had come to rue it first.”

Hal Brands, a professor at Johns Hopkins SAIS and senior fellow at AEI, writes in Foreign Affairs about the consequences of an “American First” foreign policy if President Trump is re-elected.

Brands’ perspective represents a modern version of the Reagan-Bush-McCain-Romney right-of-center American foreign policy point of view, which has much less of a market among Republican voters today.

The likely more receptive audience to Brands’ point of view are moderate Democrats and disaffected Republican voters who approve of President Biden’s handling of foreign policy.

Brands asks:

“What would become of the world if the United States became a normal great power?”

In other words, what if, under a second Trump presidency, the United States: “rejected the idea that it has a special responsibility to shape a liberal order that benefits the wider world”?

This idea has more or less guided American foreign policy across both parties since the end of the World War II. Brands reminds us of America’s position today, which a direct reflection of the world we made nearly 80 years ago:

“Today, the United States is less powerful, relative to its competitors, than it was in 1945 or 1991. But American power still underpins what order the world enjoys. Just ask Ukraine, which would have been crushed by Russia without the arms, intelligence, and money Washington provided. Or ask the European countries clinging to NATO for protection against the Russian threat. In Asia, there is no coalition that can check Chinese power without U.S. participation. In the Middle East, recent events serve as a reminder that only the United States has the ability to defend vital sea-lanes and coordinate a regional defense against Iranian attacks.”

But Brands’ ‘retrenchment’ thesis is not optimistic:

The results would not be pretty. A more normal U.S. foreign policy would produce a world that would also be more normal—that is, more vicious and chaotic. An “America first” world could be fatal for Ukraine and other states vulnerable to autocratic aggression. It would release the disorder U.S. hegemony has long contained.

Yet the United States itself might not do so badly — at least for a while — in a world where raw power matters more because the liberal order has been gutted. And even if things really fell apart, Americans would be the last ones to notice. “America first” is so seductive because it reflects a basic truth. The United States would ultimately suffer in a more anarchic world—but between now and then, everyone else would pay the greater price.

More specifically:

Eventually, of course, the United States would pay a higher price. If China were someday able to dominate East Asia after American retrenchment, it might gain the power to coerce the United States economically and diplomatically, even if it could never invade militarily…. In the meantime, the international economic friction created by protectionism and chaos would drag down American growth, which could exacerbate social and political conflicts at home.

In the ugliest scenario — but one that historians would immediately recognize — the United States would ultimately decide that the collapse of global order did require it to reengage, but from a significantly worse position, once matters within Eurasia had spun out of control. Yet it might take quite a while for this to happen. When the United States pulled back after World War I, it took a generation for the world to unravel so completely that Washington felt compelled to reengage. Until disaster struck, and the balance of power collapsed in Europe and Asia simultaneously, cascading disorder convinced most Americans to stay out of global affairs, rather than get back in. The same characteristics that insulate the United States from the deterioration of world order in the near term mean that Washington can wait a long time until that deterioration becomes intolerable.

Full article is here.

Walter Russell Meade, WSJ: “America Hits the Global Snooze Button”

I wanted to highlight Walter Russell Meade’s column from the WSJ published last week and is entitled, “America Hits the Global Snooze Button.” I would put Meade in a similar right-of-center category as Brands, but probably more explicitly anti-Biden yet not outwardly in favor of Trump (much like the WSJ Editorial Page). He warns:

Many Americans still don’t fully grasp how serious the international situation has become. Iran has set the Middle East ablaze, Russia is advancing in Ukraine, and China is pursuing pressure campaigns against Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines.

Even more challenging times lie ahead. While Washington and its allies try to calm things and return the world to something like normalcy, the revisionists are strengthening their cooperation and mobilizing their societies and economies for war.

…

The economic and potentially the military might of America and its allies far surpasses what the revisionists can bring to the table. Yet the U.S. and its allies are politically and militarily unprepared for war in the short to medium term. The revisionists therefore want to escalate crises around the globe without triggering an overwhelming response as, for example, Japan did by bombing Pearl Harbor in 1941. Against this pressure, they reason, the disorganized allies will retreat, conciliate and appease.

So far, that bet has paid off. Russia is winning its uneven contest with the West. Iran, despite the sudden death of President Ebrahim Raisi, is on a roll in the Middle East. China’s relentless campaign of small-scale menacing acts, known as “gray-zone aggression,” is eroding America’s power in the Far East.

…

To avoid [trapping America between losing choices], some argue that the U.S. should simultaneously confront our adversaries across all three theaters. But we lack the military resources for such a strategy. Even if we had the necessary capabilities, American public opinion isn’t yet united or focused enough for an effort as serious and consuming as the Cold War. Count on the revisionists to use everything in their propaganda tool kit to postpone America’s awakening—and extend their hour of opportunity.

Security analysts generally believe that relatively modest defense increases by Washington could stabilize the military balance. That, plus a mix of more forceful American diplomacy and deeper cooperation with key allies, might halt the slide to war.

Team Biden, unfortunately, would rather starve the military and embrace the diplomacy of retreat. There is an off-ramp for every provocation, a search for a “diplomatic solution” to every military attack.

This can’t last. Our adversaries have ambitious goals. We face an increasingly successful and ambitious assault on the U.S.’s international position. Either we and our allies recover our military might and political will, or our foes will fatally undermine the edifice of American power and the international order that depends on it.

I understand this perspective but 1) I don’t entirely agree with it; and 2) it offers a kind of message that is counterproductive.

The thing I admired most about Matt Pottinger’s interview with Tim Ferriss was how he emphasized Senator Arthur Vandenberg’s adage that politics should stop at the water’s edge. It might be a naive proposition in 2024 but it’s why this blog exists. As Pottinger explained:

It means we can have bitter debates internally between left and right, Democrats, Republicans, independents, Trump, Biden, but when it comes to our national interest, there must be a general consensus that prevails that we are on the same team, and that there needs to be some predictability and continuity in our policies.

And in fact, by and large, even that still continues to some extent. You have bitter fights over things like what should our approach be to Iran? But you also have strong alliances. We’ve got NATO. It’s probably the most successful multilateral alliance in world history, and you’ve seen it strengthened by Putin’s attack on Ukraine. President Biden’s meeting with the Japanese Prime Minister. We’ve got a very strong relationship with Japan, with South Korea, with Australia, the Philippines, and those things serve us well. Those are our shields that protect us.

David Leonhardt, NYT: A New Centrism Is Rising in Washington

In a similar vein as Pottinger, I wish Biden would come out and say all the things that Trump got right — and policies that Trump made the case for that Biden is implementing and that have agreement across the aisle.

Indeed, there is a new, somewhat awkward, emerging “Washington consensus” that rejects the Reagan/Clinton view on democracy and free-trade.

As David Leonhardt explains in the NYT:

But in a country that is supposed to have a gridlocked federal government, the past four years are hard to explain. These years have been arguably the most productive period of Washington bipartisanship in decades.

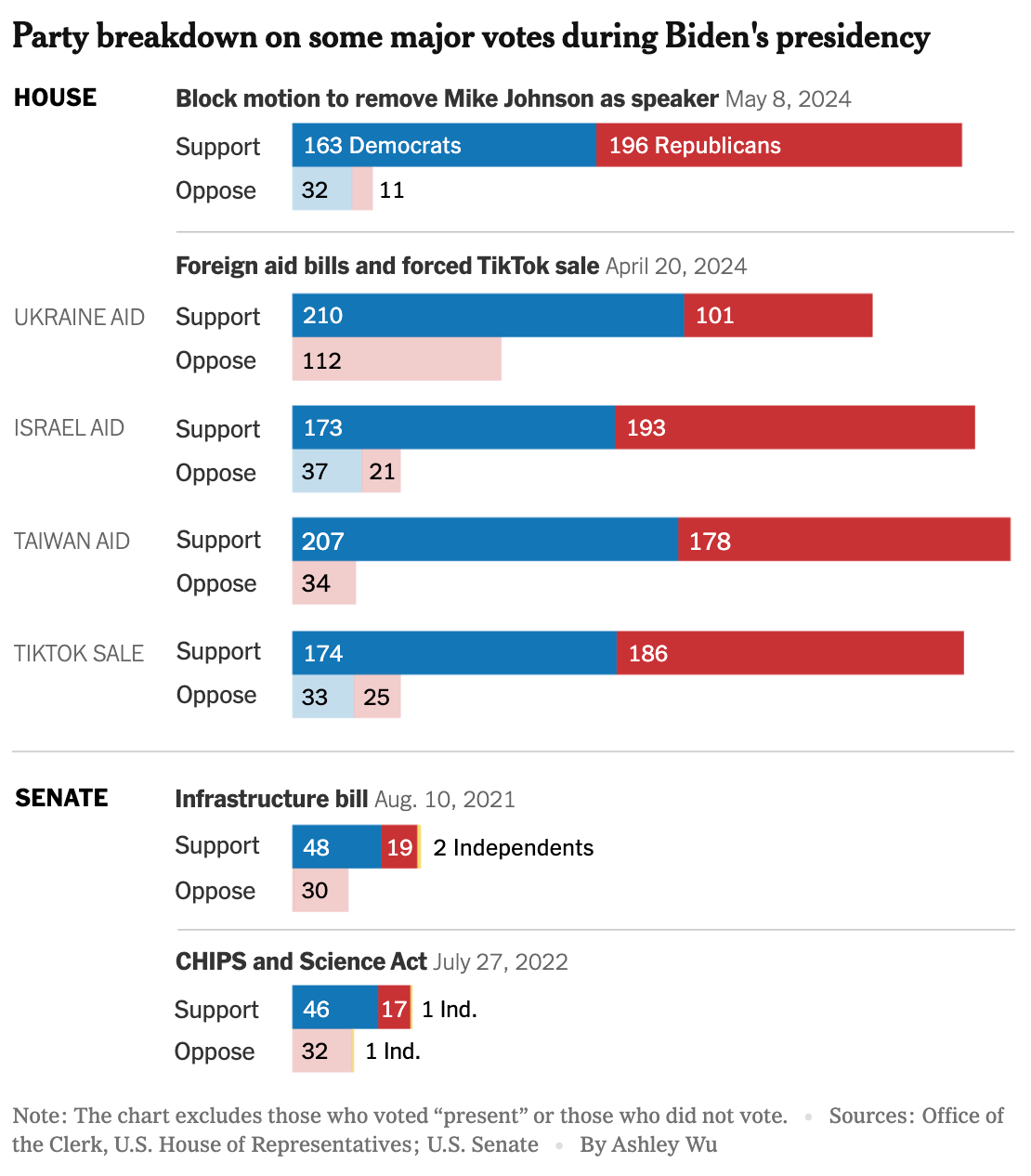

During the Covid pandemic, Democrats and Republicans in Congress came together to pass emergency responses. Under President Biden, bipartisan majorities have passed major laws on infrastructure and semiconductor chips, as well as laws on veterans’ health, gun violence, the Postal Service, the aviation system, same-sex marriage, anti-Asian hate crimes and the electoral process. On trade, the Biden administration has kept some of the Trump administration’s signature policies and even expanded them.

The trend has continued over the past month, first with the passage of a bipartisan bill to aid Ukraine and other allies and to force a sale of TikTok by its Chinese owner. After the bill’s passage, far-right House Republicans tried to oust Speaker Mike Johnson because he did not block it — and House Democrats voted to save Johnson’s job. There is no precedent for House members of one party to rescue a speaker from the other. Last week, the House advanced another bipartisan bill, on disaster relief, using a rare procedural technique to get around party-line votes.

This flurry of bipartisanship may be surprising, but it is not an accident. It has depended on the emergence of a new form of American centrism.

The very notion of centrism is anathema to many progressives and conservatives, conjuring a mushy moderation. But the new centrism is not always so moderate. Forcing the sale of a popular social app is not exactly timid, nor is confronting China and Russia. The bills to rebuild American infrastructure and strengthen the domestic semiconductor industry are ambitious economic policies.

…

As was the case during the 20th century, another important factor is an international rivalry. Then, it was the Cold War. Now, it is the battle against an emerging autocratic alliance that is led by China and includes Russia, North Korea, Iran and groups like Hamas and the Houthis.

“China is a unifying force, absolutely,” Senator Susan Collins, a Maine Republican, told me. Senator John Fetterman, a Pennsylvania Democrat, compared the rise of artificial intelligence to the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957, which led to bipartisan legislation on education and scientific research. Anxiety about A.I., Fetterman added, made possible the passage of the semiconductor-chips bill. “We are most able to come together when we acknowledge the risks we have to the American way of life,” Fetterman said. “Whose side are you on — democracy or Putin, Hamas and China?”

Once again, Eric Peters, but from his April 7 wknd notes:

China has built enough hypersonic anti-ship missiles and exported a sufficient volume of cheap fentanyl and TikTok propaganda for America to deliver a different kind of thank-you note. The US now cares more about stranding China’s vast productive capacity (and denying it cutting edge technologies) than almost anything else. In an election year, it is Washington’s only real issue with bipartisan agreement.